Research

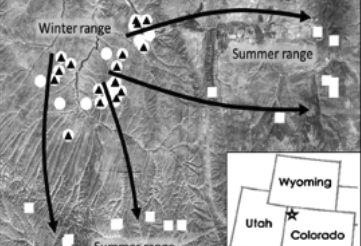

Is ungulate migration culturally transmitted? Evidence of social learning from translocated animals

Ungulate migrations are assumed to stem from learning and cultural transmission of information regarding seasonal distribution of forage, but this hypothesis has not been tested empirically. We compared the migratory propensity of bighorn sheep and moose translocated into novel habitats with that of historical populations that had persisted for hundreds of years. While individuals from historic populations were largely migratory, translocated individuals initially were not. After multiple decades, however, translocated populations gained knowledge about surfing green waves of forage (tracking plant phenology) and increased their propensity to migrate. Our findings indicate that learning and cultural transmission are the primary mechanisms by which ungulate migrations evolve. Loss of migration will therefore expunge generations of knowledge about the locations of high-quality forage and likely suppress population abundance.

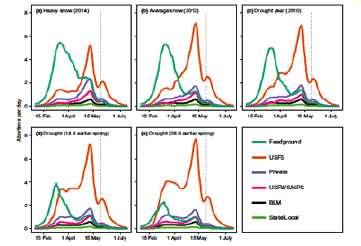

SPRING PLANT GROWTH CAN INFLUENCE BRUCELLOSIS TRANSMISSION

Brucellosis is a naturally occurring pathogen in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem most commonly known for affecting elk, bison, and cattle by causing pregnant animals to miscarry. In many systems, temporal disease dynamics may be slower than environmental conditions that alter how animals move on the landscape. That is why we decided to conduct a mathematical model-based study to predict how elk (Cervus canadensis) infected with brucellosis might behave under environmental conditions that change daily and annually (such as plant phenology and snow depth). We used these predictions to better understand how spring phenology (green up) influences the risk of brucellosis transmission from elk, through miscarried foetuses, to livestock in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem (GYE). In this study region, roughly 700 elk miscarry per year. We found that weather and plant phenology influence elk movement. And thus, as we predicted, weather and phenology alter where elk miscarry and thus where brucellosis transmission risk is highest. For example, during early snowmelt or winter drought years, up to 190 more miscarriages may occur within grazing allotments on US Forest Service leases than in heavy snow years (an increase of 85%). Meanwhile, we found that the risk of brucellosis transmission on private lands was relatively unaffected by annual weather patterns. These findings were incorporated into a comprehensive mapping tool that enables managers to identify where proactive management can mitigate the risk of elk transmitting brucellosis to cattle on shared year-round range.

Merkle, J.A., Cross, P.C., Scurlock, B.M., Cole, E.K., Courtemanch, A.B., Dewey, S.R. and Kauffman, M.J., 2017. Linking spring phenology with mechanistic models of host movement to predict disease transmission risk. Journal of Applied Ecology.

Mule Deer Surf the Green Wave

Migration has been commonly viewed as the movement between two distinct seasonal ranges. But the migration corridor that ungulates travel between seasonal ranges also provides migratory ungulates with resources. One way of understanding the influence of these resources is through the Green Wave Hypothesis (GWH). The GWH provides a conceptual framework to understand how the movements of herbivores during migration are timed to respond to pulses of high-quality forage. The GWH suggests that migratory movements enable ungulates to prolong their exposure to high-quality forage and thereby gain more energy. The way in which the green wave (spring green-up) progresses across the landscape is a concept referred to as the ‘greenscape’. When ungulates move in response to the greenscape, staying on the edge of the greenscape, it is called ‘surfing’. This study proposes the Greenscape Hypothesis wherein the speed, duration, and order of green-up along a migration route influences the ability of animals to surf green waves of forage. In this study, 99 adult female mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) located in western Wyoming were collared with GPS units. The data collected was used to understand how deer timed their movements along the migration route during peak green-up. The findings indicate that green-wave surfing plays an important role in the foraging strategy of mule deer, and that access to plant green-up along the migratory route is a key foraging benefit of migration. The study suggests that researchers and conservationists ought to expand their view of migration to include the foraging value of moving along the corridors themselves, in addition to the traditional focus on seasonal ranges.

Aikens E.O., M.J. Kauffman, J.A. Merkle, S.P.H. Dwinnell, G.L. Fralick and K.L. Monteith. 2017. The greenscape shapes surfing of resource waves in large migratory herbivore. Ecology Letters 20:741-750.

MIGRATION DISTANCE MATTERS

Within a single herd or population, individual animals can migrate a wide range of distances. For example, mule deer in the Red Desert of Wyoming migrate anywhere from 20 to 264 km. Of the 28 mule deer we tracked with GPS, 26% were classified as short-distance (<50 km), 44% as moderate-distance (50-100 km), and 30% as long-distance migrants (>100 km). Long-distance migrants spent 100 additional days migrating compared with those that migrated short or moderate distances. In fact, long-distance migrants spent nearly one-third of the year migrating, which supports the emerging science that migration routes function not only as travel corridors, but also as key foraging habitats in both spring and autumn. Given the amount of time dedicated to migration, long-distance migrants also spent 70 fewer days on winter range. Exposure to anthropogenic mortality risks, like highways and fences, was much higher for long-distance migrants, whereas short and moderate-distance migrants were more vulnerable to harvest. In short, there were clear differences in winter residency, migration duration, and risk of anthropogenic morality among short-, moderate-, and long-distance migrants.

Pronghorn and Mule Deer Use of Underpasses and Overpasses

The seasonal migrations of ungulates are increasingly threatened by roads, fences, and other infrastructure. Although roadway impacts (e.g., wildlife–vehicle collisions and landscape permeability) to species such as mule deer can largely be mitigated with underpasses and continuous fencing, similar mitigation may not be effective for pronghorn or other ungulate species that are reluctant to move through confined areas. The Wyoming Department of Transportation recently installed 6 underpasses and 2 overpasses along 20 km of U.S. Highway 191 in western Wyoming, USA, where we evaluated species-specific preferences by documenting the number of migratory mule deer and pronghorn that used adjacent overpasses and underpasses for 3 years following construction. We documented 40,251 crossings of the highway by mule deer and 19,290 crossings by pronghorn. Of those highway crossings, 79% of mule deer moved under, whereas 93% of pronghorn moved over the highway. These strong species-specific differences were evident at both sites and support the notion that overpasses are more amenable to pronghorn than underpasses. Our results highlight that species-specific preferences are an important consideration when mitigating roadway impacts with wildlife crossing structures.

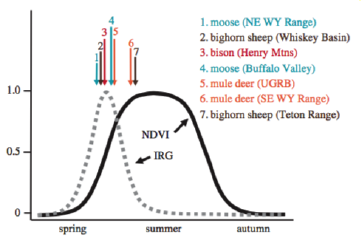

LARGE HERBIVORES SURF WAVES OF GREEN UP DURING SPRING

It can be time-consuming and impractical to do field research to identify when forage quality peaks annually across large landscapes. Knowing this, researchers increasingly use remotely sensed metrics to study spring green-up. In this study, we wanted to understand whether multiple species of large herbivores were capable of seeking out forage patches when they were at peak green-up. We used a common measurement for spring green-up, the Instantaneous Rate of Green-up (IRG). We coupled IRG data with a movement modelling framework and relocation data collected during the green-up period from two populations each of bighorn sheep (Ovis canadensis), mule deer (Odocoileus hemoinus), elk (Cervus elaphus canadensis), moose (Alces alces), and bison (Bison bison). Data came from populations in western Wyoming and eastern Utah, and 463 individuals were monitored for 1–3 years from 2004 to 2014. Seven of the ten populations selected habitat patches where the plants were at peak green-up, although some populations appeared to select for either the leading or trailing edge of the green-up curve. This multi-species study largely supports the critical assumption of the green wave and forage maturation hypotheses: herbivores move to track plants at intermediate biomass (when plants have sprouted and are most nutritious) by selecting habitat patches at peak green-up. In conclusion, we found that IRG is a useful tool for linking herbivore movement with plant phenology. These results pave the way for advancing our understanding of how animals track resource quality that varies across space and time.

Merkle, J.A., K.L. Monteith, E.O. Aikens, M.M. Hayes, K.R. Hershey, A.D. Middleton, B.A. Oates, H. Sawyer, B.M. Scurlock, M.J. Kauffman. 2016. Large herbivores surf waves of green-up in spring. Proceedings of the Royal Society B 283:20160456.

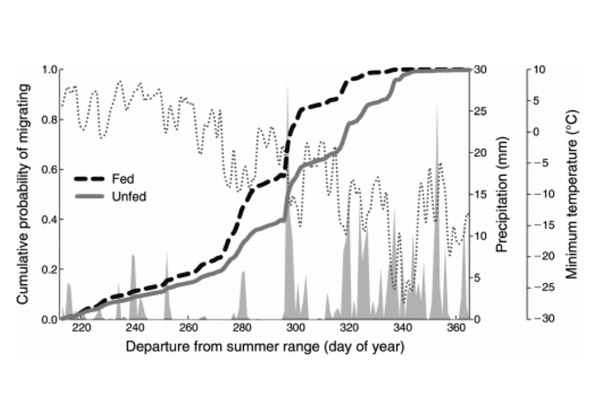

HOW SUPPLEMENTAL FEEDING INFLUENCES ELK MIGRATION

Numerous factors currently threaten long-distance migrations, such as, climate change, anthropogenic barriers (e.g., roads), habitat loss, and changes in resource distribution (e.g., agricultural fields, supplemental feeding). We assessed the influence of supplemented feeding during winter on the year-round migratory behavior of North American elk using GPS data from 219 adult female elk. Our study tested the assumption that elk attending feedgrounds (hereafter referred to as ‘‘fed’’) would employ a different migratory tactic than elk utilizing native winter range (hereafter referred to as‘‘unfed’’). Our analysis revealed that, as predicted, the migratory behavior of fed and unfed elk differed. Fed elk migrated 19.2 km further, spent 11 more days on stopover sites, arrived at summer range 5 days later, resided on summer range 26 fewer days, and departed in the autumn 10 days earlier than unfed elk. We found that fed and unfed elk had different sensitivities to environmental factors that drive migration, including snow melt and vegetation green-up. Our findings suggest that management practices applied in one season may have unintended behavioral consequences in subsequent seasons. Although our results indicate that winter feeding has changed patterns of elk migration, we also found that supplemental feeding has not yet altered the propensity of fed elk to migrate. Although supplemental feeding has the potential to reduce private property damage and maintain or increase herd size by enhancing overwinter survival, our study indicates that winter feeding has carryover effects on elk foraging ecology and seasonal range use that should be considered when evaluating this management action.

Jones, J.D., M.J. Kauffman, K.L. Monteith, B.M. Scurlock, S.E. Albeke, and P.C. Cross. 2014. Supplemental feeding alters migration of a temperate ungulate. Ecological Applications 24(7): 1769-1779.

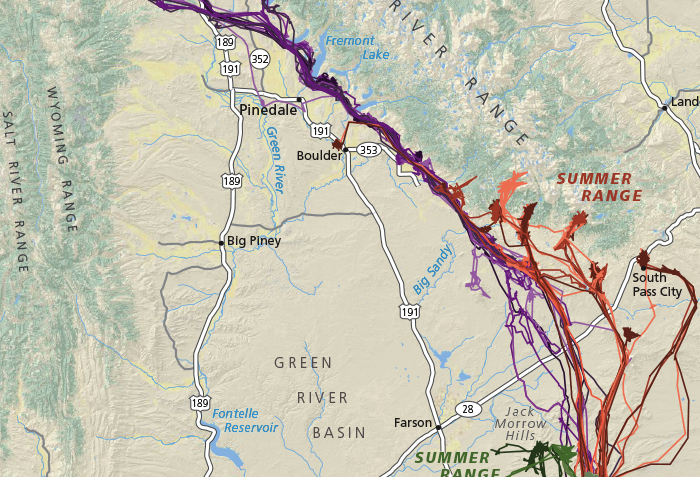

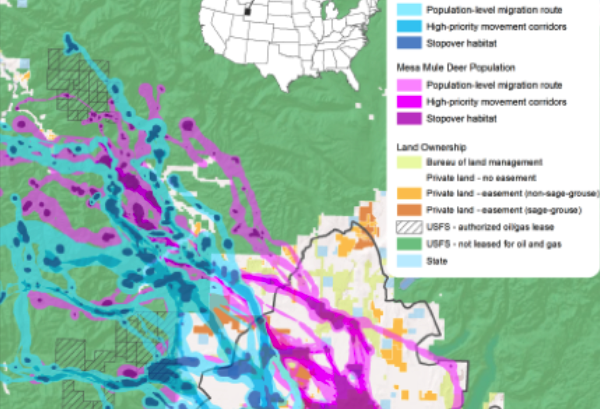

Conserving migratory mule deer through sage-grouse habitat protection

The upper Green River Basin (GRB) of western Wyoming supports some of the largest sage-grouse and mule deer populations in North America. The GRB has suffered dramatic declines in both species, concurrent with recent natural gas development. Meanwhile, sage-grouse have been proposed as an umbrella species for other sagebrush-dependent fauna. Indeed, sage-grouse conservation measures have the potential to protect important mule deer migration routes and seasonal ranges. To assess whether sage-grouse conservation could conserve mule deer migration corridor habitat, we collected GPS data from two populations of migratory mule deer and calculated individual and population-level migration routes. We then conducted spatial analyses to determine what proportion of mule deer migration routes, stopover areas, and winter ranges were located in areas managed for sage-grouse conservation under the Wyoming Core Area Policy (WCAP). We found that approximately half of the area comprised of corridors and stopover sites overlaps with habitats protected as sage-grouse core areas. Furthermore, the sage-grouse core areas overlap nearly all of the winter ranges for mule deer. However, disturbance thresholds set within the WCAP must be biologically tolerable to mule deer for conservation efforts of sage-grouse to provide protection to mule deer corridors. Our analysis revealed gaps in protection for mule deer migration corridors potentially conserved through sage-grouse conservation. In particular, conservation efforts on private lands hold promise to conserve migration corridors by connecting sage grouse core areas with Forest Service lands where many mule deer go for summer.

Copeland, H.E., H. Sawyer., K.L. Monteith, D.E. Naugle, A. Pocewicz, N. Graf, and M.J. Kauffman. 2014. Conserving migratory mule deer through the umbrella of sage-grouse. Ecosphere 5(9).

MULE DEER MIGRATION MAY JUMP GREEN WAVE, DEPENDING ON FORAGE QUALITY AND LANDSCAPE DISTURBANCE

Migratory ungulates make recurring movements, often along traditional routes between seasonal ranges. These migrations allow individuals to follow seasonal changes in food quality, phenology, or availability. Whether ungulates accomplish such movements by “surfing” (e.g., following the edge of green-up) or “jumping” (e.g., migrating ahead of green-up) to enhance their consumption of high-quality forage, has been a topic of considerable interest, because of the need to better understand factors that underpin migration in large herbivores. By combining indices of vegetation greenness (Normalized Difference Vegetation Index; NDVI), and diet quality (fecal nitrogen), we were able to test for influences of forage quality on mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) movement patterns. Doing so would enable us to determine whether mule deer surf or jump the green wave. In this study, 100 adult (≥1.5 years old) female mule deer located in the the Piceance Basin near northwest Colorado were collared with Global Positioning Systems (GPS) to track migratory movement. A collection of 340 fecal samples were obtained using known wintering grounds and locating mule deer either visually or by radio-telemetry. We analyzed the deer’s movements and compared their migrations to when and where plant nutritional quality was highest (based on fecal nitrogen samples and remotely sensed greenness). We found that, as expected, vegetation greenness increased throughout spring. We did learn that greenness was primarily influenced by snow depth (when snow was present) and secondarily by temperature. Fecal nitrogen was lowest in samples collected when deer were on winter range, indicating the lowest-quality of forage was on winter ranges. Fecal nitrogen increased rapidly during migration. It remained relatively high when deer were on summer range, indicating the forage quality was higher along the migration corridor and on summer range. We also found that fecal nitrogen and NDVI values corresponded along the migration corridor. These results indicate spring migration for mule deer provided a way for these large mammals to increase access to a high-quality diet by following patterns of vegetation growth. This population of mule deer “jumped” rather than “surfed” the green wave. They arrived on summer range well before peak productivity of forage occurred. Jumping, or making a rapid migration to summer range, may enable pregnant females to arrive on birthing areas prior to giving birth, locate critical resources, seek seclusion from others, give birth, and then become mobile, with their offspring, on summer range just as the plants there are reaching their peak nutritional value. This strategy could increase female mule deer’s ability to meet nutrient demands associated with lactation. In addition, previous research indicates that mule deer increase their rate of movement when migrating through disturbed landscapes, which may also account for the “jumping” behavior observed in this study. Whether a mule deer population is surfing or jumping the green wave during spring migration, our study provides evidence that there is a potential for benefits in each migration strategy, or a combination of the two.

Lendrum, P.E., C.R. Anderson, Jr., K.L. Monteith, J.A. Jenks, and R.T. Bowyer. 2014. Relating the movement of a rapidly migrating ungulate to spatiotemporal patterns of forage quality. Mammalian Biology 79: 369-375

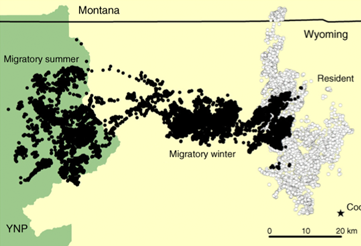

Drought and Predation Effects on Elk Migrations

Migration is a striking behavioral strategy by which many animals enhance resource acquisition while reducing predation risk. Historically, the demographic benefits of such movements made migration common, but in many taxa the phenomenon is considered globally threatened. Here we describe a long-term decline in the productivity of elk (Cervus elaphus) that migrate through intact wilderness areas to protected summer ranges inside Yellowstone National Park, USA. We attribute this decline to a long-term reduction in the demographic benefits that ungulates typically gain from migration. Among migratory elk, we observed a 21-year, 70% reduction in recruitment and a 4-year, 19% depression in their pregnancy rate largely caused by infrequent reproduction of females that were young or lactating. In contrast, among resident elk, we have recently observed increasing recruitment and a high rate of pregnancy. Landscape-level changes in habitat quality and predation appear to be responsible for the declining productivity of Yellowstone migrants. From 1989 to 2009, migratory elk experienced an increasing rate and shorter duration of green-up coincident with warmer spring–summer temperatures and reduced spring precipitation, also consistent with observations of an unusually severe drought in the region. Migrants are also now exposed to four times as many grizzly bears (Ursus arctos) and wolves (Canis lupus) as resident elk. Both of these restored predators consume migratory elk calves at high rates in the Yellowstone wilderness but are maintained at low densities via lethal management and human disturbance in the year-round habitats of resident elk. Our findings suggest that large-carnivore recovery and drought, operating simultaneously along an elevation gradient, have disproportionately influenced the demography of migratory elk. Many migratory animals travel large geographic distances between their seasonal ranges. Changes in land use and climate that disparately influence such seasonal ranges may alter the ecological basis of migratory behavior, representing an important challenge for, and a powerful lens into, the ecology and conservation of migratory taxa.

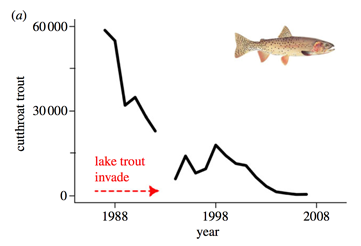

Food Webs and Migration

The loss of aquatic subsidies such as spawning salmonids is known to threaten a number of terrestrial predators, but the effects on alternative prey species are poorly understood. At the heart of the Greater Yellowstone ecosystem, an invasion of lake trout has driven a dramatic decline of native cutthroat trout that migrate up the shallow tributaries of Yellowstone Lake to spawn each spring. We explore whether this decline has amplified the effect of a generalist consumer, the grizzly bear, on populations of migratory elk that summer inside Yellowstone National Park (YNP). Recent studies of bear diets and elk populations indicate that the decline in cutthroat trout has contributed to increased predation by grizzly bears on the calves of migratory elk. Addition- ally, a demographic model that incorporates the increase in predation suggests that the magnitude of this diet shift has been sufficient to reduce elk calf recruitment (4–16%) and population growth (2–11%). The disruption of this aquatic–terrestrial linkage could permanently alternative species interactions in YNP. Although many recent ecological changes in YNP have been attributed to the recovery of large carnivores—particularly wolves—our work highlights a growing role of human impacts on the foraging behaviour of grizzly bears.

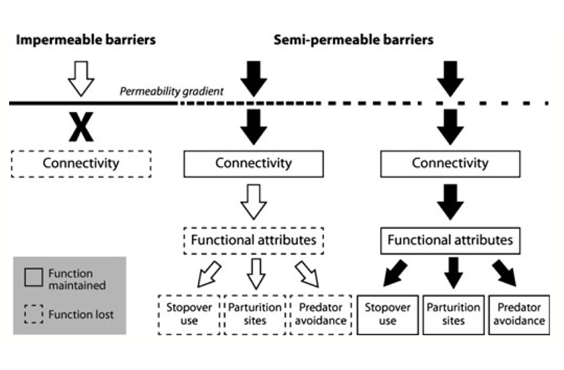

Semi-permeable barriers and migration

1. Impermeable barriers to migration can greatly constrain the set of possible routes and ranges used by migrating animals. For ungulates, however, many forms of development are semi-permeable, and making informed management decisions about their potential impacts to the persistence of migration routes is difficult because our knowledge of how semi-permeable barriers affect migratory behaviour and function is limited.

2. Here, we propose a general framework to advance the understanding of barrier effects on ungulate migration by emphasizing the need to (i) quantify potential barriers in terms that allow behavioural thresh olds to be considered, (ii) identify and measure behavioural responses to semi-permeable barriers and (iii) consider the functional attributes of the migratory land-scape (e.g. stopover s) and how the benefits of migration might be reduced by behavioural changes.

3. We used global position system (GPS) data collected from two sub populations of mule deer Odocoileus hemionus to evaluate how different levels of gas development influenced migratory behaviour, including movement rates and stopover use at the individual level , and intensity of use and width of migration route at the population level . We then characterized the functional landscape of migration routes as either stopover habitat or movement corridors and examined how the observed behavioural changes affected the functionality of the migration route in terms of stopover use.

4. We found migratory behaviour to vary with development intensity. Our results suggest that mule deer can migrate through moderate level s of development without any notice able effects on migratory behaviour. However, in areas with more intensive development, animals often detoured from established routes, increased their rate of movement and reduced stop- over use, while the overall use and width of migration routes decreased.

5. Synthesis and applications. In contrast to impermeable barriers that impede animal movement, semi -permeable barriers allow animals to maintain connectivity between their seasonal ranges. Our results identify the mechanisms (e.g. detouring, increased movement rates, reduced stopover use) by which semi-permeable barriers affect the functionality of ungulate migration routes and emphasize that the management of semi-permeable barriers may play a key role in the conservation of migratory ungulate populations.

Crossing structures for migratory mule deer

Wildlife–vehicle collisions pose a major safety concern to motorists and can be a significant source of mortality for wildlife. Additionally, roadways can impede movements and reduce habitat connectivity. For migratory ungulates, these problems can be exacerbated when roadways bisect migration routes, as is the case in Southwest Wyoming, USA, where a 21-km section of U.S. Highway 30 overlaps with a critical winter range and migration route used by thousands of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus). In an effort to reduce deer–vehicle collisions (DVC) and maintain migratory connectivity, the Wyoming Department of Transportation installed 7 concrete box-culvert underpasses with continuous game-proof fencing between each crossing structure. To evaluate the effectiveness of this mitigation project, we used remote cameras to quantify the number of mule deer that used the underpasses, estimate passage rates through time, and compare rates of DVCs before and after underpass construction. Through 3 years of monitoring (which encompassed autumn migration [2008, 2009, and 2010], winter use, and spring migration [2009, 2010, and 2011] for 3 migration cycles), we documented 49,146 mule deer move through the underpasses. Passage rates of deer approaching underpasses steadily increased from 54% in Year 1 to 92% in Year 3. Peak movements during the autumn migration occurred in mid-December, while peak spring movements were in mid-March and early May. Underpass and fence installation effectively reduced DVCs by 81%. Had fence gates remained closed and cattle guards clear of snow, DVCs could be eliminated altogether. Our results suggest that underpasses, combined with game-proof fencing, can improve highway safety for motorists while providing safe and effective movement corridors for large populations of migratory mule deer.

Influence of Elk Migration on Wolf Habitat Use

Identifying the ecological dynamics underlying human–wildlife conflicts is important for the management and conservation of wildlife populations. In landscapes still occupied by large carnivores, many ungulate prey species migrate seasonally, yet little empirical research has explored the relationship between carnivore distribution and ungulate migration strategy. In this study, we evaluate the influence of elk (Cervus elaphus) distribution and other landscape features on wolf ( Canis lupus ) habitat use in an area of chronic wolf– livestock conflict in the Greater Yellowstone Ecosystem, USA. Using three years of fine-scale wolf ( n ¼ 14 ) and elk ( n ¼ 81) movement data, we compared the seasonal habitat use of wolves in an area dominated by migratory elk with that of wolves in an adjacent area dominated by resident elk. Most migratory elk vacate the associated winter wolf territories each summer via a 40 – 60 km migration, whereas resident elk remain accessible to wolves year-round. We used a generalized linear model to compare the relative probability of wolf use as a function of GIS- based habitat covariates in the migratory and resident elk areas. Although wolves in both areas used elk-rich habitat all year, elk density in summer had a weaker influence on the habitat use of wolves in the migratory elk area than the resident elk area. Wolves employed a number of alternative strategies to cope with the departure of migratory elk. Wolves in the two areas also differed in their disposition toward roads. In winter, wolves in the migratory elk area used habitat close to roads, while wolves in the resident elk area avoided roads. In summer, wolves in the migratory elk area were indifferent to roads, while wolves in resident elk areas strongly avoided roads, presumably due to the location of dens and summering elk combined with different traffic levels. Study results can help wildlife managers to anticipate the movements and establishment of wolf packs as they expand into areas with migratory or resident prey populations, varying levels of human activity, and front-country rangelands with potential for conflicts with livestock.

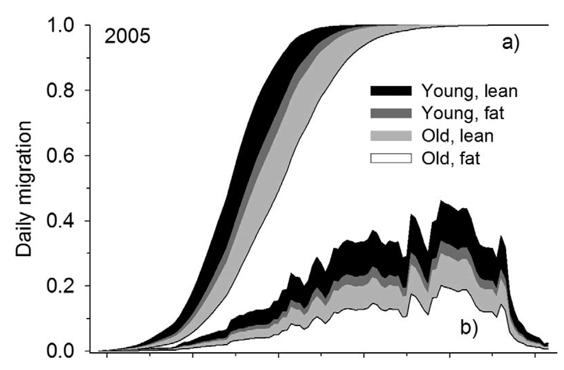

Timing of mule deer migration

Phenological events of plants and animals are sensitive to climatic processes. Migration is a life-history event exhibited by most large herbivores living in seasonal environments, and is thought to occur in response to dynamics of forage and weather. Decisions regarding when to migrate, however, may be affected by differences in life-history characteristics of individuals. Long-term and intensive study of a population of mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) in the Sierra Nevada, California, USA, allowed us to document patterns of migration during 11 years that encompassed a wide array of environmental conditions. We used two new techniques to properly account for interval-censored data and disentangle effects of broad-scale climate, local weather patterns, and plant phenology on seasonal patterns of migration, while incorporating effects of individual life- history characteristics. Timing of autumn migration varied substantially among individual deer, but was associated with the severity of winter weather, and in particular, snow depth and cold temperatures. Migratory responses to winter weather, however, were affected by age, nutritional condition, and summer residency of individual females. Old females and those in good nutritional condition risked encountering severe weather by delaying autumn migration, and were thus risk-prone with respect to the potential loss of foraging opportunities in deep snow compared with young females and those in poor nutritional condition. Females that summered on the west side of the crest of the Sierra Nevada delayed autumn migration relative to east-side females, which supports the influence of the local environment on timing of migration. In contrast, timing of spring migration was unrelated to individual life-history characteristics, was nearly twice as synchronous as autumn migration, differed among years, was related to the southern oscillation index, and was influenced by absolute snow depth and advancing phenology of plants. Plasticity in timing of migration in response to climatic conditions and plant phenology may be an adaptive behavioral strategy, which should reduce the detrimental effects of trophic mismatches between resources and other life-history events of large herbivores. Failure to consider effects of nutrition and other life-history traits may cloud interpretation of phenological patterns of mammals and conceal relationships associated with climate change.

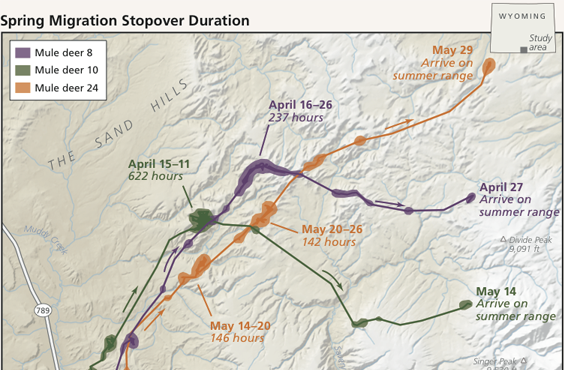

Stopover ecology of a migratory ungulate

1. Birds that migrate long distances use stopover sites to optimize fuel loads and complete migration as quickly as possible. Stopover use has been predicted to facilitate a time-minimization strategy in land migrants as well, but empirical tests have been lacking, and alternative migration strategies have not been considered.

2. We used fine-scale movement data to evaluate the ecological role of stopovers in migratory mule deer Odocoileus hemionus – a land migrant whose fitness is strongly influenced by energy intake rather than migration speed.

3. Although deer could easily complete migrations (range 18–144 km) in several days, they took an average of 3 weeks and spent 95% of that time in a series of stopover sites that had higher for-age quality than movement corridors. Forage quality of stopovers increased with elevation and distance from winter range. Mule deer use of stopovers corresponded with a narrow phenological range, such that deer occupied stopovers 44 days prior to peak green-up, when forage quality was presumed to be highest. Mule deer used one stopover for every 5.3 and 6.7 km travelled during spring and autumn migrations, respectively, and used the same stopovers in consecutive years.

4. Study findings indicate that stopovers play a key role in the migration strategy of mule deer by allowing individuals to migrate in concert with plant phenology and maximize energy intake rather than speed. Our results suggest that stopover use may be more common among non-avian taxa than previously thought and, although the underlying migration strategies of temperate ungulates and birds are quite different, stopover use is important to both.

5. Exploring the role of stopovers in land migrants broadens the scope of stopover ecology and recognizes that the applied and theoretical benefits of stopover ecology need not be limited to avian taxa.

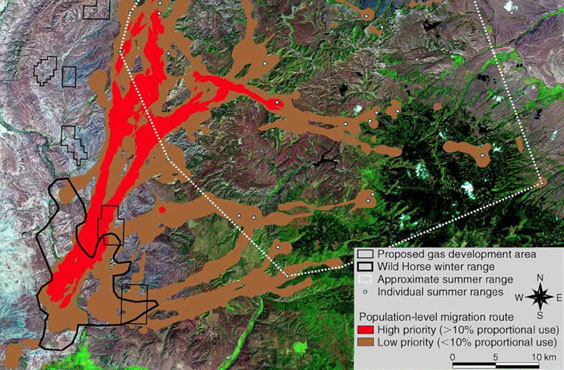

Prioritizing migration routes for conservation

As habitat loss and fragmentation increase across ungulate ranges, identifying and prioritizing migration routes for conservation has taken on new urgency. Here we present a general framework using the Brownian bridge movement model (BBMM) that: (1) provides a probabilistic estimate of the migration routes of a sampled population, (2) distinguishes between route segments that function as stopover sites vs. those used primarily as movement corridors, and (3) prioritizes routes for conservation based upon the proportion of the sampled population that uses them. We applied this approach to a migratory mule deer (Odocoileus hemionus) population in a pristine area of southwest Wyoming, USA, where 2000 gas wells and 1609 km of pipelines and roads have been proposed for development. Our analysis clearly delineated where migration routes occurred relative to proposed development and provided guidance for on-the-ground conservation efforts. Mule deer migration routes were characterized by a series of stopover sites where deer spent most of their time, connected by movement corridors through which deer moved quickly. Our findings suggest management strategies that differentiate between stopover sites and movement corridors may be warranted. Because some migration routes were used by more mule deer than others, proportional level of use may provide a reasonable metric by which routes can be prioritized for conservation. The methods we outline should be applicable to a wide range of species that inhabit regions where migration routes are threatened or poorly understood.